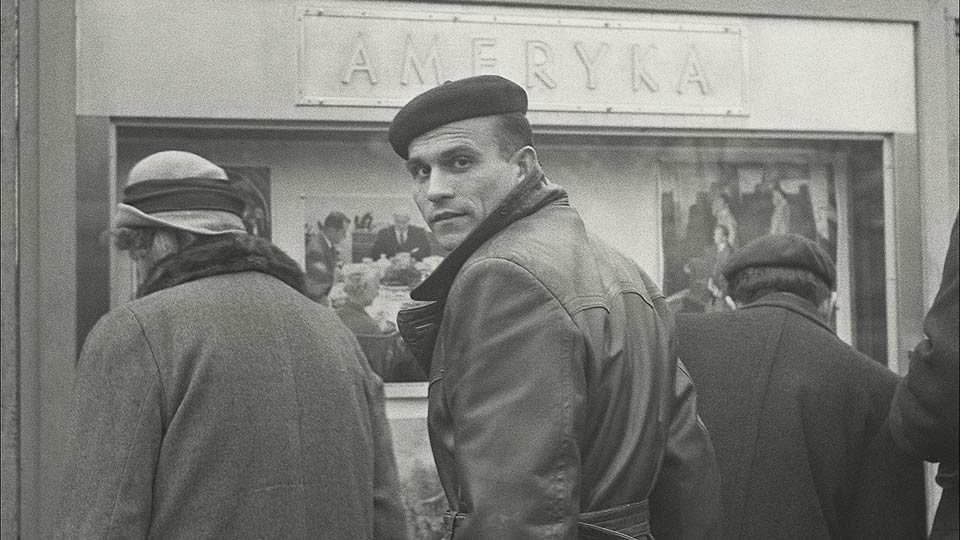

What was Poland like in the 1960s? What was ordinary life like for its citizens, in an otherwise unremarkable part of Eastern Europe, who had for decades been held hostage to international events? During Hilter’s invasion and the Nazi occupation of the 1930s and 40s, followed by the socialist era in which Poland was subsumed by the USSR at the end of the war, Poland wasn’t a sovereign state. Its relative poverty and the yoke of Communism meant it was left behind, perhaps forgotten, as western European countries rebuilt and flourished after the war.

International Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski turned his attention to his own country and spent some time in the early 1960s visiting rural, remote parts of his homeland, examining the effect on the national psyche of oppression and poverty. The result is Nobody Leaves, a collection of seventeen vignettes that capture an essence of daily life in a Poland still shackled to the agricultural past and weighed down by the inhuman Soviet machine.

Kapuscinski is a delightful writer. In approaching social commentary, there is perhaps a touch of Orwell about him. Yet Orwell, who was also a journalist, wrote with great clarity and immediacy, and didn’t shy away from polemics. In Kapuscinski, the reader finds a writer keener to leave an impression and paint a picture. There is strong use of metaphor, and dramatic licence in ascribing motivation to characters. How much of it is a fictionalised or at least partly imagined account of the people he met on his travels?

The grim tone and atmosphere of Nobody Leaves is sustained throughout, and there is little room for humour, nor even for reflection. The book is not a diatribe against Communism, but more of an observance of what is, rather than what may be. As such, Nobody Leaves can feel oddly detached and dispassionate, and some of the short chapters feel thematically similar to others.

The Stiff is a macabre first person account as the narrator helps to carry the coffin of an eighteen year-old boy who has been killed in a mining accident. A Survivor on a Raft introduces Mister Jagielski, a young raftsman disconnected from world events, who has no capacity to do other than to ply his manual labour upon the water. In The Fifth Column on the March, two elderly women escape from an old people’s home to enjoy a musical concert. We meet farmers, musicians and friends. There are philosophical asides about success, family, and the differences between the urban and the rural. Over relatively few pages, Kapuscinski asks some fundamental questions, yet poses no easy answers.

The title piece, Nobody Leaves, stands as a metaphor for the difficulty in getting out of Poland, or even more specifically, out of poverty, which is a theme of the book. It is an examination of a dysfunctional family. The parents and the son live with a day-to-day simmering triangle of hostility, but the family remains a unit because none has a choice or a way out. It is a microcosm of the country at large, where people are not free.

Running to only 111 pages, Nobody Leaves is a concise snapshot of Socialist-era Poland, where each of the self-contained chapters runs for around five pages. The publication by Penguin marks its debut in English, even though this collection appeared in Polish in 1962. If you are familiar with Kapuscinski’s later work such as The Shadow of the Sun, or if you are fascinated by Twentieth Century world history, then you’ll find a lot to enjoy in Nobody Leaves. It can also be commended for the author’s literary merit and crispness of style.

Publisher: Penguin Modern Classics Date Published: 7th February 2019