Margaret Atwood is said to prefer ‘speculative fiction’ rather than ‘science-fiction’ as the genre allocated to her 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale. That didn’t stop it winning all kinds of science-fiction awards, but it falls into the same bracket as other dystopian novels that imagine a society close enough to our own yet fundamentally different, such as we find in Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World.

Margaret Atwood is said to prefer ‘speculative fiction’ rather than ‘science-fiction’ as the genre allocated to her 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale. That didn’t stop it winning all kinds of science-fiction awards, but it falls into the same bracket as other dystopian novels that imagine a society close enough to our own yet fundamentally different, such as we find in Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World.

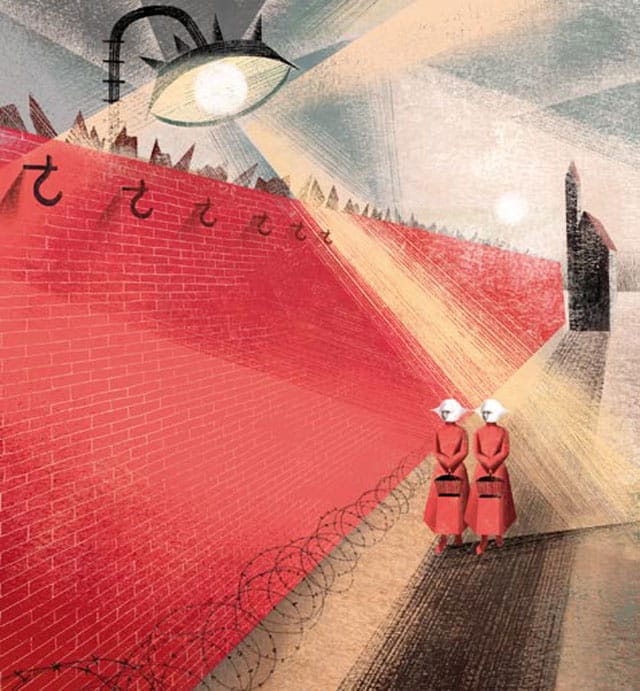

The story is told by Offred, a woman who lives in the Republic of Gilead as a ‘handmaid’ – a social class of fertile women whose purpose is to bear a child for the often-sterile wives of the ruling classes, under an assigned male. Her daily life is described in some detail, and since the theocratic regime is fairly new (Offred remembers the days of personal liberty and the husband she was taken from) she is also keen to point out to the reader the various strictly-observed customs and dress codes. As with any brutal system of governance that stifles individualism as well as free thought and expression, the Republic of Gilead is an austere, inhuman place, and its oppressed citizens are dry, humourless and afraid.

The author’s preferred genre of ‘speculative fiction’ ends up feeling misplaced because the events depicted in the book ought to resonate as tragically real. The book was published only a few years after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, when the liberty of women was curtailed once the parties of god regressed the state under its misogynistic theocratic regime. There is very little feeling, if any, in The Handmaid’s Tale to suggest it was an exploration of world events that saw the freedom of women denied that inspired the writing. Rather, the object of Atwood’s ire seems to be the religious right in America, which certainly remains a negative force to be reckoned with even to this day, but whose attitude towards women is hardly likely to inspire anything comparable to Gilead.

The author’s preferred genre of ‘speculative fiction’ ends up feeling misplaced because the events depicted in the book ought to resonate as tragically real. The book was published only a few years after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, when the liberty of women was curtailed once the parties of god regressed the state under its misogynistic theocratic regime. There is very little feeling, if any, in The Handmaid’s Tale to suggest it was an exploration of world events that saw the freedom of women denied that inspired the writing. Rather, the object of Atwood’s ire seems to be the religious right in America, which certainly remains a negative force to be reckoned with even to this day, but whose attitude towards women is hardly likely to inspire anything comparable to Gilead.

If the satirical target is misplaced, or at the very least, played safe, then so too is the antagonism depicted in the novel’s events. Atwood’s working assumption seems to be that men are the problem, but none of the male characters is brought to life by the writer to a sufficient extent to justify this premise. There is little palpable insight into the male, or even into conservative religious psychology. Offred’s former husband is dimly and distantly remembered, and thinly sketched out, as is ‘the Commander’ – the ‘Fred’ to whom she is now assigned. Male characters are not provided the reach of becoming either antagonists or allies; they are only described.

A lauded feminist classic the book may be, but perhaps its lack of balance and depth, given over instead to constantly reinforcing the same point that subjugating women is not good for society (to which few sane people would disagree), leaves it with a smaller natural readership that it otherwise might enjoy. Orwell knew his subject matter in and out. He knew the psychology of the hard left because he was steeped in leftism himself. He knew how Marxist ideology would translate into action under Stalin and the consequences that could be measured in terms of human suffering. The world of 1984 is disturbingly real because Orwell understood it. The Handmaid’s Tale lacks such richness and insider knowledge, and, despite its literary merit, feels cold, drab and unsurprising by comparison.

A new production of The Handmaid’s Tale, starring Elisabeth Moss (Mad Men) hits TV screens soon. The new edition of the novel, released by The Folio Society, comes with colour illustrations by Anna and Elena Balbusso.

A new production of The Handmaid’s Tale, starring Elisabeth Moss (Mad Men) hits TV screens soon. The new edition of the novel, released by The Folio Society, comes with colour illustrations by Anna and Elena Balbusso.

Publisher: The Folio Society Release Date: April 2017