The East of West Theatre Company’s resurrection of The Slave – the controversial 1964 play by LeRoi Jones (now known as Amari Baraka) – is perfectly timed for Black History Month but it was an ill-judged decision to unleash such a powerful spirit within the confines of the intimate Tristan Bates Theatre in Covent Garden.

The East of West Theatre Company’s resurrection of The Slave – the controversial 1964 play by LeRoi Jones (now known as Amari Baraka) – is perfectly timed for Black History Month but it was an ill-judged decision to unleash such a powerful spirit within the confines of the intimate Tristan Bates Theatre in Covent Garden.

The small, studio playhouse was ideal for adding to the tension and claustrophobia of the siege unfolding on stage but many of us in the upper half of the tiered seating had to contend with an obstructed view.

The only part of Sophie Thomas’ set which was visible for the duration of the play was a centrally-positioned sofa, pushed up against a back wall as part of a homely, yet barely furnished parlour. A chair and side cabinet were located to its right, but all action in this area was blocked by a sea of heads.

Director Rachel Hayburn would be wise to rethink the position of the characters in key scenes – particularly the floor work at the end – although quite how she could achieve that within such a cosy theatre is difficult to conclude.

Midway through the one-act production, I was painfully aware of feeling as trapped and frustrated as the married, white couple onstage. Grace (Samantha Coughlan) and Bradford Easley (Bradford Easley) were being held at gunpoint in their home by a black intruder, Walter Vessels (Stanley J. Brown). This former poet was once mentored by Bradford and married to Grace – a union which produced two children.

The use of atmospheric lighting added to the strain, coupled with the sound of detonating bombs at regular intervals – distant echoes of a violent race war that was triggered by Walter, the leader of the Black Liberation Army. As the revolution slowly blasted its way towards the Easley’s home, it was matched flare for fiery flare by the characters’ blistering tempers as they debated love and hate, oppression and pity.

Fifteen minutes before the play reached a conclusion, a few audience members decided to produce their mobile phones to check the time and their emails. The light from the screens jarred against the inky darkness of the theatre and illuminated the apathy of those seated in the upper tiers.

In truth, the lack of respect towards the three actors on stage can be blamed on many factors, not only the venue. Topping this list would be the nature of Baraka’s characters. He was arguably eager to steer the audience towards despising Grace, Bradford and Walter from the outset.

Our introduction to the Easleys followed their arrival home and the subsequent discovery of their intruder. Exactly where they went in the midst of their neighbourhood turning into a war zone was unspecified but that matters little. Their willingness to leave the kids alone with an army of angry revolutionaries on their doorstep immediately highlighted how little there was to like about this hollow, self-serving couple. Their reactions to Walter only added to our distain; he is a ‘madman’ who needs to be stopped before he ‘kills another white person’.

Walter was no more endearing: brandishing a gun and holding a family hostage while getting slowly half cut on bourbon seemed far from heroic. His homophobic slurs were as abhorrent as the Easley’s racial insults. Walter’s passionate and often contradictory outbursts served to emphasise how the whites had pushed him to lead a revolution, but being holed up at the Easley home, drinking and demanding his kids while his black brothers were getting killed on the front line was arguably selfish.

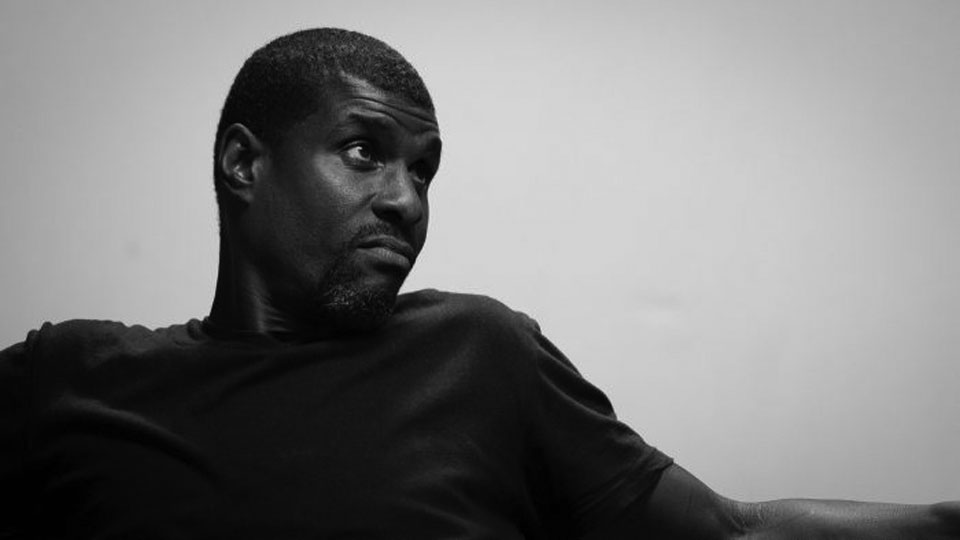

I cannot judge the cast on their performance as I didn’t get to see most of their expressions but Stanley J. Brown, as Walter, emerged as my favourite. Best known for his work as Othello, his dialect occasionally slipped during his calmer lines but his rage-fuelled exchanges with Stephen MacNiece’s Bradford made for engaging listening. Also, his monologue was delivered in my line of sight and he made eye contact to hold my attention.

Running at just over one hour in length, expect to be drawn deeply into murky shades of grey as the narrative of this seminal play unfolds. This story of black versus white, of the oppressed versus his oppressor, is far from clear cut and Baraka’s theme is just as relevant today as it was over 50 years.

With post-Brexit hostility towards Europeans rising in the UK, religious wars still raging in pockets of the world and controversial events in the US giving cause for a Black Lives Matter movement, The Slave serves as a reminder of both how far and how disappointingly little we seem to have come in the years since its debut.

A provocative, unapologetic look at racism and inequality, The Slave deserves to be seen but make sure you take a seat in the lower rows of the Tristan Bates Theatre to fully absorb its stark message.

Cast: Stanley J. Brown, Samantha Coughlan, Stephen McNiece Theatre: Tristan Bates Theatre Writer: LeRoi Jones / Amari Baraka Director: Rachel Heyburn Duration: 65 mins Performance Dates: 11th – 29th October 2016