They say all publicity is good publicity. With the brouhaha over free speech on university campuses and a television interview so disastrous (for the interviewer) it had to be seen to be believed, we were keen to check out the work of the Canadian academic caught up in the middle of it. Jordan B Peterson’s new book – 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos – stays in the bestseller list and his public lectures sell out in minutes. By reading the book, we wanted to see if we could figure out why a clinical psychologist and professor of psychology from the University of Toronto has suddenly gained rock star appeal amongst a burgeoning admirer base, and at the same time become one of the most divisive public intellectuals around today.

They say all publicity is good publicity. With the brouhaha over free speech on university campuses and a television interview so disastrous (for the interviewer) it had to be seen to be believed, we were keen to check out the work of the Canadian academic caught up in the middle of it. Jordan B Peterson’s new book – 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos – stays in the bestseller list and his public lectures sell out in minutes. By reading the book, we wanted to see if we could figure out why a clinical psychologist and professor of psychology from the University of Toronto has suddenly gained rock star appeal amongst a burgeoning admirer base, and at the same time become one of the most divisive public intellectuals around today.

The premise of the book is simple enough: in each of twelve chapters, Peterson sets out a clearly-stated rule, and then goes on to explain why it will help to keep you straddling the correct distance between order and chaos. Is it a self-help book? Well, sort of, and there are plenty of people who claim Peterson’s publicly-available lectures have changed their lives for the better; but it certainly doesn’t come with any prescriptions, things to try at home, false hope or easy answers. Nor is it a trite recipe for happiness. The gist of Peterson’s tome is that life must be meaningful, and how that is defined will depend upon the individual, but twelve simple rules can help you make good life decisions, even when they come with the cost of pain or sacrifice. Do not bother children when they are skateboarding explains why kids need to hurt themselves and get back up on their feet, and why parents shouldn’t try to fight all their battles for them and overprotect them, for example.

There’s much more to the book than learning life skills, and the format is that Peterson explains what he means by his basic rule, then shows how it applies on a much larger scale and what previous thinkers have said on the subject, before ratcheting up to a satisfying conclusion and finally restating the rule so that you then say to yourself, “Ah, now I get it!” Do not bother children when they are skateboarding takes the reader on a journey into the terrors of Communism and the malevolent consequences of post-modernist ideologies. It has to be said that there are always perfectly logical trains of thought leading from premise to thesis, but there are times where the literary flair feels like the equivalent of jazz music – you’ve no idea how you were taken there, but you enjoyed the journey. This is especially acute if you don’t finish a whole chapter in a single sitting. Readers unsure about taking magical mystery tours through human psychology, history and mythology probably won’t derive as much pleasure from this volume: it’s more for readers who get excited by following ideas wherever they lead and maybe learning something new – or at least a new way of looking at things – along the way.

Some sections were standouts for us. The world would be an infinitely better place if every parent and prospective parent was forced to read and obey, Do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them. It had us nodding along in agreement with every razor-sharp observation on how parental responsibility and old-fashioned ideas of punishment and discipline acted as bulwarks against the tyrannous free-reign of tiny dictators. Assume that the person you are listening to might know something you don’t is another simple idea that has become so regrettably lost in an era of bifurcated views, ideological tribalism and an assumption of evil about anyone who disagrees with you. Everyone would benefit from this kind of tolerance and developed intellectual integrity, especially Channel 4 news presenters.

We loved that the book is full of wise saws and modern instances. Philosophers such as Nietzsche and Socrates are referenced approvingly, as well as Russian writers Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn, all of whom have strongly influenced Peterson’s thinking. Others such as Derrida and Sartre are used as examples of where bad thinking takes you. These moments we thoroughly enjoyed. As a Christian with a strong interest in religion, Peterson also uses stories from the Old and New Testaments to make his cases, which will be off-putting to some, but it was the Disney references we found less appealing… There are examples to cater to most tastes. The anecdotal stories are another strong feature of the book. There are insights into Peterson’s profession as a clinical psychologist and the particular issues of people he has treated, as well as tales (not always cheerful ones) of friends or people he has known throughout his life, as well as his immediate family. These personal touches provide a great warmth and help keep the reader hooked.

Peterson makes no claim that the ideas expressed in the book are particularly new, and he cites the history of ideas explicitly. The views he expounds can also be seen as old-fashioned. Yet the overall impression on reading the book is that it’s refreshingly original. Why is that? Perhaps it’s because, in an age of stale homogeneity, voices running against the accepted wisdom like Peterson’s are increasingly rare, and often seen as threatening for that reason. Stand up straight with your shoulders back is a chapter on social hierarchies, why they exist, and why that’s a good thing: 12 Rules for Life is unlikely to find its way onto a university’s Gender Studies reading list any time soon.

Whatever your political views, the content is good and useful, expressed with great enthusiasm by the author. It may even have the power to transform the lives of readers not already too set in their ways. Being told to grow up, accept responsibility for your life and make sure your kids aren’t infantilized is rather a harsh message, but the author delivers it with aplomb, and in the absence of condescension. Peterson is a beacon of light shining in an ocean of sterile guff. That’s why 12 Rules for Life is an unlikely (on the face of it) bestseller.

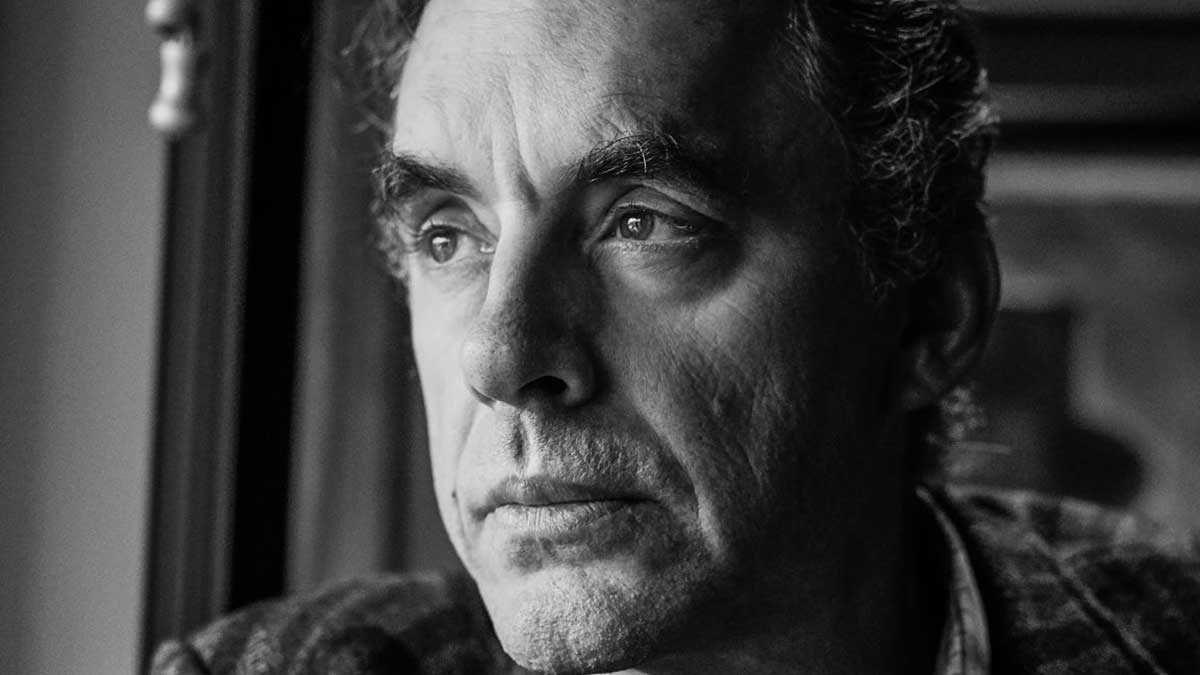

It turns out there is substance behind the handsomely saturnine face (Daniel Day-Lewis for the biopic?). We found a few hundred pages rummaging around inside of Jordan Peterson’s mind a thrilling tour that was in turns exhilarating and frustrating, but never, ever dull. I guess you could say we derived meaning from the experience. And that can only be a good thing. Like all good reads, it left us wanting more.

Publisher: Allen Lane Publication Date: 16th January 2018

[rwp-reviewer-rating-stars id=”0″]